With meat-reduction diets rising in Australia, driven by increasing awareness of the health and environmental benefits of eating less meat, alternative proteins are on the rise – including cultured and cultivated meat products. Researchers in Japan have recently found a way to use photosynthetic microorganisms to produce cultured meat in a more sustainable way.

There is a pressing need for environmentally friendly meat production technologies to tackle the increasing global food demand. Cultured meat production is one such technology that is attracting a lot of attention as an alternative to conventional meat production.

First developed in 2012, cultured meat is an emerging food type that can provide sustainable animal protein, using scaffolds and 3D materials to develop products with similar shape and structural properties to traditional meats.

Since 2013, the industry has attracted nearly US$3 billion in private investment, and over 150 new companies have been established to develop innovative food products through cell biology and advanced biomanufacturing techniques.

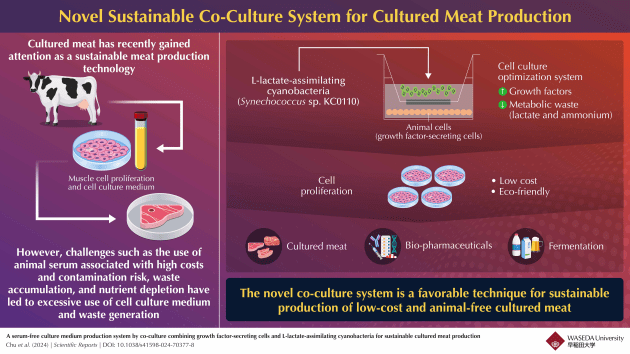

Cultured meat is grown from animal muscle cells, and animal serum (liquid part of blood) is required to promote the growth of these cells. However, the use of serum poses significant challenges because of its high cost and associated ethical concerns.

Now, researchers have developed a system where growth factor-secreting liver cells and photosynthetic microorganisms can be grown together to create a low cost, environmentally friendly medium to grow muscle cells without the use of animal serum.

A research team led by Professor Tatsuya Shimizu from Tokyo Women’s Medical University have developed a new system for culturing muscle cells without serum by using photosynthetic microorganisms. The findings were published in Scientific Reports on 23 August.

Animal serum provides proteins called growth factors that are essential for the growth of muscle cells. However, rat liver cells are also known to secrete these growth factors. The researchers discovered that the medium remaining after culturing these liver cells (or the supernatant) contains growth factors, and can support muscle cell growth without the use of serum.

“Our study provides a novel low cost, sustainable cell culture system with broad applicability in various fields involving cellular agriculture, such as cultured meat production, fermentation, bio-pharmaceutical production, and regenerative medicine,” said Shimizu.

“Further, as a technology for producing meat without killing animals, culturing animal cells with photosynthetic microorganisms could help address not only future food security challenges, but also ethical concerns and issues related to climate change.”

The study addressed one of the challenges associated with this method of production.

“Although more growth factor-secreting cells and longer cultivation produces larger amounts of growth factors, the downside is that the cells also produce waste products like lactate and ammonia into the medium at the same time, which eventually hinders muscle cell growth,” said Shimizu.

Hence, waste removal is crucial to improve the performance of this culture supernatant as an alternative to animal serum. To resolve this, the researchers had developed L-lactate assimilating cyanobacteria (photosynthetic microorganisms) with lactate to pyruvate converting genes.

These organisms are capable of taking in harmful waste metabolites, such as lactate and ammonia, and converting them into nutrients for animal cells (rat liver cells and muscle cells), such as pyruvate and amino acids.

In the study, the research group proposed a new system in which the growth-factor secreting rat liver cells would be co-cultured with the modified cyanobacteria, and the supernatant from this co-culture could then be used to promote muscle cell growth without serum.

They found that co-culturing cyanobacteria with the rat liver cells resulted in a 30 per cent reduction of lactate and over 90 per cent reduction of ammonia. Additionally, the nutrients produced by the cyanobacteria were able to reduce the nutrient depletion by rat liver cells, resulting in an abundance of nutrients like glucose and pyruvate in the co-culture supernatant compared to the supernatant collected from where rat liver cells were grown alone.

When this co-culture supernatant was used to cultivate muscle cells, they found that the growth rate of muscle cells was three times higher than the growth seen when only rat liver cells were used. This demonstrates that co-culturing cyanobacteria significantly enhances the performance of the culture supernatant as a serum alternative and optimises cell culture through waste upcycling.

Other recent research into cultured meat has focused on the flavour profile, with researchers in Korea using a flavour-switchable scaffold that can release meaty flavour compounds at cooking temperatures, to replicate the taste of conventional meat products.

As alternative proteins are on the rise, it will be interesting to see the implementation of new methods to create consumer products.