University of Adelaide research has found that, when used as a natural additive, the mucilage of two native plantago species make gluten-free bread more elastic, which results in “softer, springier” and “fluffier” loaves with more volume.

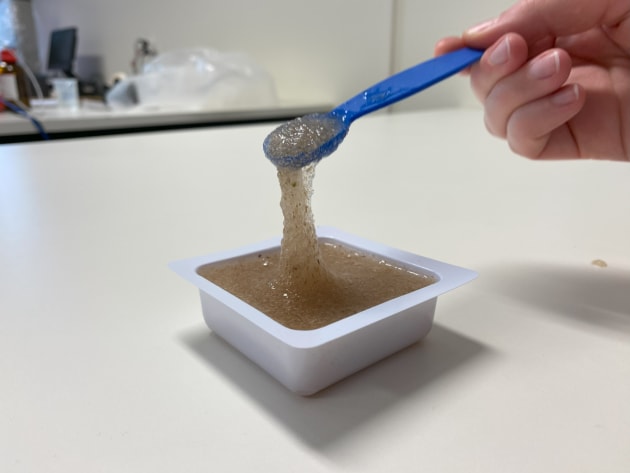

Mucilage is a sticky gel of pure dietary fibre that is produced by many seeds when they are wetted.

The research was led by Dr James Cowley, who has studied plantago seeds for more than a decade.

“Consumers consider texture and appearance to be critical to their perception of a quality gluten-free bread, and they are looking for springy, airy loaves that behave as closely to gluten-containing breads as possible,” Cowley said.

He added that demand is also growing for gluten-free bread products without long ingredients lists.

“Consumers are increasingly looking for clean label products that are perceived as ‘healthier’ or ‘more natural’,” Cowley said.

“Hydroxypropylmethylcellulose, known as HPMC or E464, is one of the most common gluten replacements in bread but is often met negatively, as it is perceived as ‘artificial’ or ‘unnatural’.

viscous stretchy behaviour that lets it

replicate some functions of gluten.

(Image: University of Adelaide)

“Psyllium husk, which is extracted from plantago ovata for use in gluten-free doughs, can be included on ingredient labels as vegetable fibre without the need for an E number, allowing it to be more ‘clean label’.”

Crowley’s research discovered the chemistry of each plantago species, their differences in mucilage content, and suitability as a food ingredient.

“The differences in mucilage led to wildly different impacts when added to gluten-free breads. Adding plantago flour made the doughs more elastic, making them more resistant to collapsing during fermentation, which made breads with better appearance and texture.

“We believe this comes down to the differing chemistries of the mucilage, as the amount alone did not explain the effects. For example, two native species, P. cunninghamii and P. turrifera, produced similar or better-quality breads to commercial P. ovata, despite having much lower mucilage content,” Crowley said.

Crowley said the research also found that whole-seed flours – using the inner seed as well as the mucilage-containing husk – were better than those with the mucilage removed.

“Commercial psyllium husk is made by removing the mucilage through a grinding process, but this produces a large amount of waste with no high-value commercial use, despite our group recently showing that the waste is high in nutrients.

“We hope that more products may use Plantago whole-seed flour, which still contains that beneficial mucilage, as a more sustainable alternative to purified psyllium husk,” Crowley said.

Cowley said and colleagues are narrowing the quality gap between gluten-free and traditional breads through follow-up research.

“My brilliant PhD student, Lucija Štrkalj, a co-author on this paper, recently successfully defended her PhD thesis and made some exciting discoveries about how the mucilage chemistry leads to more elastic networks in food products.

“We are now beginning to understand why mucilage chemistry plays a big role in improving the quality of gluten-free breads made with plantago flour.

“We aren’t quite there yet, but new additives and formulations appear all the time. Hopefully one day we can produce clean-label gluten-free breads that are just as good as the real thing,” Cowley said.

The research has been published in Food Hydrocolloids.