A major new initiative to tackle the challenges in Australian food systems is being launched today. Food System Horizons is a partnership between the national science agency, CSIRO, and The University of Queensland, with backing from industry, policy makers, and food support agencies.

Food System Horizons goal is to use multidisciplinary science and research to improve our food system, and with it our health, environment, society, and economy.

From there, Food System Horizons, will be better equipped to help Australians understand the food system, their roles in it, and who they need to work with to develop a more sustainable, nutritious, and equitable food system.

What is a food system

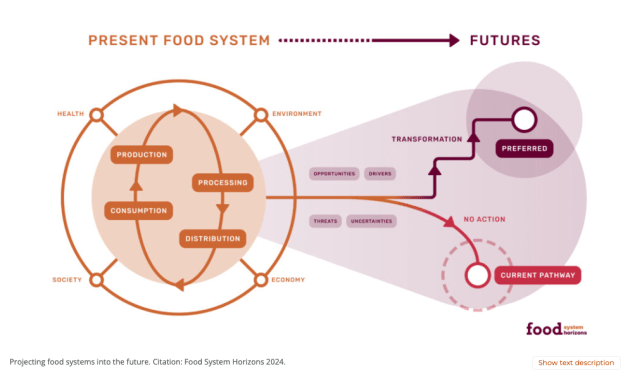

The term food system refers to all the interconnected components that are required to feed people – production, processing, transport, distribution, marketing, consumption, and waste – as well as the associated activities, people, and inputs.

The interactions of these parts with the drivers of change in the food system make it very fluid. The food system that results impacts our health, the environment, our society, and the economy.

A systems perspective

CSIRO’s Dr Rohan Nelson said Australians need to start thinking differently about their food systems if we want them to be sustainable into the future.

“We are opening up a dialogue right across Australia – from government to industry and the general consumer – covering everything from food production, processing, distribution, marketing, consumption and waste management.

“Taking a systems perspective will also us to better understand the big picture and what we need to do to safeguard our food systems for the future,” said Nelson.

CSIRO and UQ said that taking a systems perspective was necessary to manage growing sustainability and social inclusion challenges.

“These challenges arise from dynamic and surprising interactions between natural resources, agriculture, food processing, distribution, nutrition and human health,” they said.

The systems approach also makes it easier to understand the present food system, interactions within it, and what we want it to look like in the future.

“It also helps us understand how we need to transform towards preferred food futures and avoid futures we do not want.”

Accelerate food system transitions by using research that has gone before

A recent paper lead by CSIRO scientists, Shortcuts for accelerating food system transitions, suggests the collective wisdom from more than two decades of sustainability transitions research be used to accelerate the transformation of global food systems – in essence, to “shortcut theory into action”.

It highlighted systemic change would never be straight forward because global food systems are “inherently complex”.

Arrows within and between circles indicate flows and interconnected parts of the system. (Source: CSIRO)

“Feeding the world’s eight billion people via globally interconnected markets and supply chains involves innumerable stakeholders with their own respective roles in the production, processing, distribution, marketing, and consumption of food. Furthermore, multiple persistent challenges impede whole systems change,” it said.

The many components in a food system form a value chain, but often, each link operates independently. Well intentioned change can also result in negative impacts elsewhere.

“The complexity of these drivers and their interactions with different parts of food systems make them highly dynamic, sometimes resulting in unintended outcomes for food security, nutrition and health, livelihoods, the environment, and the economy. However, if considered holistically these same drivers can progress change.

“The inherent complexity of the food system sets the context for the challenges of pursuing change,” the authors said.

They outline a triple challenge of change – change resistance, narrow technological focus, and feasibility.

“Firstly, investment in the existing system makes change untenable, creating resistance. Secondly, narrow focus on technologies and practices may ignore aspects that a given solution may need to succeed but can also negatively impact the rest of the system. Thirdly, ambitious solutions – particularly those that require rapid, widespread, and significant changes – are frequently unfeasible.”

It outlined three lessons:

Align Reinforcing processes

Creating an “enabling context” – phasing out unsustainable systems while preparing stimulating conditions for new systems – can drive change, e.g. government policy stimulus, economic incentivisation, and phasing out of old systems.

“Food system transitions likewise require multiple processes to co-align in a way that reinforces and then catalyses further change. This includes overcoming economic barriers and dependency on industrial agriculture, changing policies that perpetuate unsustainable food systems, while harnessing emerging interventions such as shifts in lifestyle, new markets, and political coalitions.

“The diverse settings in which food systems operate necessitate timely and place-based interventions, specific to local and regional aspirations, resources available, and different cultural, political, and biophysical environments.”

Integrate robust intervention pathways

Over the last decade, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) have been implemented. While they were developed as stand-alone goals, the 2023 report showed spillovers between them, revealing the complexity of transitions in how interlinked SDGs require integrated changes in technology, policy, and societal behaviours.

Food systems can learn from the complexities revealed by the SDGs and develop diverse transition pathways coordinated with sectors beyond food to integrate health, finance, labour, trade, and resources to realise benefits and mitigate unintended consequences.

“To ensure robustness, pathways in food systems also need to be prepared to adjust to changing conditions and future uncertainties. A range of decision and planning tools from integrated assessment and areas like climate change adaptation can support the design of adaptive pathways for food systems to improve durability through future systemic risks and viability long term.”

Experiment to build support for uptake

Food systems can experiment with intervention pathways to gather evidence on suitability in practice and build support for wider rollout. This can mean experimenting with farming models (e.g. agroecological systems), new technologies (e.g. food processing to improve nutritional quality), policy tools (e.g. taxing certain foods), business/partnership models (e.g. blockchain-based platforms for farmer-to-consumer direct sales), and finance mechanisms (e.g. mobilising private capital through food finance architecture). The development of the organic foods niche during the 1990s is an example of experimentation and learning.

For more information click here.