Food waste is an endemic issue in Australia. The latest report from the Fight Food Waste CRC examines meat waste and domestic refrigeration. Research fellow Dr Bhavna Middha, from the Centre of Urban Research at RMIT University, Melbourne, provides insights on how stakeholders can work together to reduce food waste.

Domestic refrigerators and freezers have evolved considerably over the last century. Not only are they ubiquitous appliances in the kitchen, by connecting to the way we shop, cook, eat, entertain, and work, they facilitate our current lifestyles.

Connectedly, food waste, including meat waste is of increasing concern, albeit belatedly in the context of climate change and diminishing biodiversity. There is a need for better understanding of how food and the use of cold storage has evolved along with our changing practices and fridge designs.

Food waste is an endemic issue in Australia. The Australian National Food Waste Strategy Baseline has identified that nearly 300kgs of food is wasted in Australia per person per year (FIAL 2021).

This equates to a total of 7.3 million tonnes of food, of which households generate 34 per cent.

Approximately 92 per cent of household food waste goes directly to landfill, which has significant environmental consequences (FIAL 2021).

Meat, one of the more expensive food items, is one of the main food waste items identified in Australian households with 140,300 tonnes of meat wasted per year in total (FIAL 2021). The greenhouse gas emissions of meat waste going into landfill adds to the emissions associated with embodied energy and resources of meat production and transport.

Key findings

Our newly released report, a pilot study conducted in conjunction with the Fight Food Waste CRC, has produced some insights towards reducing food waste that could save the average family between $2200 and $3800 per year (FIAL 2021).

Our study took a quantitative and a qualitative social practices approach to go beyond psychological understandings of individual behavioural change and mere technological solutions.

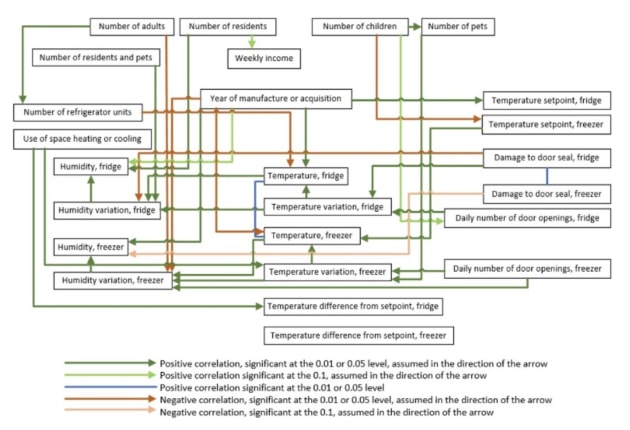

Using temperature and humidity monitoring devices, interviews and fridge rummages, we have produced an evidence base that provides detailed and varied ways in which food and meat is consumed and wasted in households, how refrigerators and freezers are used and how this shapes food waste. We found that:

Householders reflexively tried to save food and especially meat from waste. The increase in prices of all essential commodities at the time of data collection has made many householders thrifty and more conscious about food waste, even if in the short term.

Managing leftovers from cooked meals and deli meat (cold cuts) was most challenging for householders, so much so that some households avoided buying deli meat.

Freezers were used to save food, especially meat from expiring at the date provided on the packaging. Householders deliberately bought meat close to the expiry date, thus saving money on specials.

Quality of meat was regarded by some householders as reduced by freezing and may have led to waste. Alternatively, freezing meat was avoided completely for this reason.

Certain kinds of meat were more prone to waste, such as deli meats and leftover barbeque meats

Many householders were unaware of temperature variations in their fridges and tended not to blame the fridge temperature when meat or food was discarded.

However, many participants noted the design of the fridge (deep, narrow shelves) prevented them from having a clear vision of their fridge, leading to them forgetting about certain stored food items.

Householders acquired knowledge about how long to store food in the fridge and how to save food from waste via packaging labels, internet searches and lived experience. This was reflected in householders having their own understanding of the number of days for which a food product or leftovers could stay in the fridge.

Entertaining and being good hosts required over catering and while the food was distributed to guests by a few householders, it led to increased leftovers stored into the fridge with some subsequently being wasted.

Date labels were used in many ways during shopping and storage: as an indication of freshness, to ascertain how long an item could be stored for, and if near expiry (and on special) buying it to save money. Some experimented and used their senses to bypass or confirm the information provided by date labels.

While the average age of refrigerator units was approaching 10 years, some households had multiple refrigerator units, each having a different purpose.

Refrigerators units with damaged door seals were rare, but, compared to the average refrigerator, were older and the fridges (but not the freezers) experienced wider temperature variations.

For some refrigerator units, average temperatures were different to the setpoint temperatures, with some being outside of the optimal range.

These recommendations are premised on the notion that merely informing householders about food waste is not an adequate strategy to bring about change in everyday routines and activities.

Interventions that enable change within the complex and interwoven lives that people live are required, as current models are not designed for multiple, complex behaviours (Quested et al. 2013).

Therefore, these recommendations are relevant to key stakeholders, including policy makers (food and retail, community building, urban planning, education, waste); product designers; product manufacturers; packaging companies; food and red meat retailers; retailers of ready to eat and pre-portioned meal ingredients; online meal subscription companies; peak bodies; and urban studies and food researchers.

Support delivery of affordable and walkable shopping options for everyday shopping to reduce the occurrence of overloading of fridges

Support the reduced dependence on domestic freezers for long term storage as a societal goal to reduce increasing appliance and energy consumption, and possible food waste.

Encourage improved manufacturer practices such as product stewardship. For example, encourage management of fridge through manufacturer’s continuous engagement with the product to undertake tasks such as updating temperature control functions, installing new alert functions, and checking door-seal damage.

Engage the community in innovation and rethinking fridge design, layout, and size in relation to fridge and freezer capacities, distinguishing between the main purposes of the primary fridge, secondary fridges, full-time fridges, and part-time fridges.

Undertake industry research with community participation on the capacity of ‘sniff’ tests to determine freshness. This could include the use of chemicals in meat processing that may disrupt or enable sensory evaluation.

Encourage and support reduction of the use of processed meat, especially refrigerated, through other means of meat preservation and provisioning.

Integrating advice to create trust in a single authority that can provide tailored and specific advice as a one-stop advice platform for cold storage and use of stored products advice. Moreover, including considerations of multicultural attributes of the population in advice on the life of food and storage. For example, specific food items may not be handled in similar ways in different households.

Shared consumer-manufacturer responsibility to communicate the appropriate fridge temperature for foods’ optimum shelf life and the expected fridge maintenance for good, long-term fridge performance.

Integrating and streamlining different packaging instructions and date labels ( for example, through peak bodies).

Tailor smart fridge technology and design with consumer practices of fridge and freezer use through co-design processes.

More qualitative research into methods to challenge societal norms such as over catering, elevated hygiene due to COVID-19 and risk of food poisoning, which address questions of ‘what is enough food for parties?’ and ‘what kind of food stays better for long in the fridge?’

More quantitative research into the frequency and nature of users’ access to the various sections of a fridge, including related energy use.